The bewildering case of the nation with By Prof. Rajneesh Narula OBE, Henley Business School

The run-up to Brexit Day has been a windfall for the chattering classes. We have known since June that this day must come, and thousands of commentators – perhaps millions, if you include the discussions in living rooms and pubs across Europe – have visualised and considered the various possible shapes Brexit might finally take; what would be gained and what might be lost, and how the future of Britain in the 21st century might unfold after B-Day. Non-Europeans are quite bewildered by the number of column inches and minutes devoted to Brexit in our newspapers, online fora and broadcast news. B-Day is still a subject for fantasy: there is even less clarity as to the UK government’s position. In short, uncertainty still abounds, and this reflects itself in the value of the Pound against most currencies. That there is so much difficulty agreeing on a withdrawal agreement does not bode well for the actual negotiations, because almost every aspect of life is shaped by the intensity of the embrace from which the UK wishes to extricate itself. Converting hundreds of years of formal and informal treaties and institutional arrangements into new law is mind-bogglingly difficult. Article 50 is a harbinger of mirthless days for all, with the possible exception of lawyers and consultants. It is a matter of incredulity to the rest of Europe that Brexit is not some practical joke, and I say the ‘rest of Europe’ because these islands will remain part of Europe, and two millennia of interaction will not suddenly stop on ‘moving-out’ Wednesday. Indeed, there is no moving-out: The UK, like some petulant teenager, is simply giving formal notice of relocation two years hence (but like all teenagers he feels he can demand things without considering the quid pro quo). But here lies the rub: this is not a petulant teenager leaving home, but the legal divorce of long-married couple who have a wide variety of common property, offspring, shared interests and responsibility, and a lot of history. To the outside observer, the UK has painted itself as the much-wronged and misunderstood teenager, while the EU has portrayed itself as the unappreciated and long-suffering spouse who is being dumped in an acrimonious and public breakup. These two contrasting views that continue to be propagated by either side assure us of a convoluted and discordant two-year negotiation. The teenager feels confident that its (estranged) extended family in the form of the commonwealth will clutch the prodigal cousin tightly to their bosom. Alas, it is already clear that Empire 2.0 is fantasy. On the other hand, the EU knows where it stands: its position is clear. The deck, to use another tired metaphor, is stacked firmly in their favour, and they know it. That they offered a Soft Brexit shortly after the referendum was a kindness, but in its spurning, little has been gained except Trump-like hubris and ill-will. B- Day brings to mind that other famous British folly, The Charge of the Light Brigade. I hope 29 March 2019 proves me wrong.

0 Comments

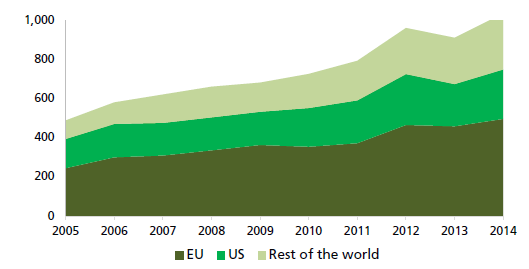

By Prof. Nigel Driffield, Warwick Business School Inward investment is of vital importance to the UK economy. Compared to other G7 countries, the UK has had the highest percentage of inward FDI as a percentage of GDP, at 64 per cent of GDP in 2014 (ONS 2016). Much of this investment is from other EU member states, as Figure1 shows.

How is inward investment likely to be affected by the UK leaving the European Union? Investors in the UK will face a number of challenges as a result of Brexit if they seek to sell into the EU and operate supply chains that cross between the UK and the UK. The devaluation in sterling will also have an impact on inward investment decisions. There will be challenges for investors if they seek to operate supply chains that cross (sometimes several times) between the UK and EU. When the single market was created in 1993, many commentators speculated that intra-EU FDI would plummet. This turned out to be far from the case as firms took advantage of the opportunities to coordinate resources across countries. The single market connects innovative firms to the richest market in the world and, through EU regional policy and structural funds, allows firms to take full advantage of location economies where labour is available in low-cost locations. Most recently, Honda has warned MPs of the consequences of leaving the customs union. From an inward investment perspective the essential problem is that the ‘middle region’ of activities of the value chain, characterised by lower value added and higher volume of employment, are often carried out outside the UK. Developed countries attempt to “plug the gap in the middle” by seeking inward investment that will generate employment for the squeezed middle. This can be achieved by identifying key sectors that hit the ‘sweet spot’ of high productivity but also employment generation. However, these sectors, such as advanced manufacturing, food technology and financial services, are the ones most vulnerable to frictions in value chains which drive away investment, due to the way they are organised in the single market.

|

Authors

Scholars from the field of International Business and other related disciplines Archives

April 2023

Categories |

Support |

© COPYRIGHT 2021. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed